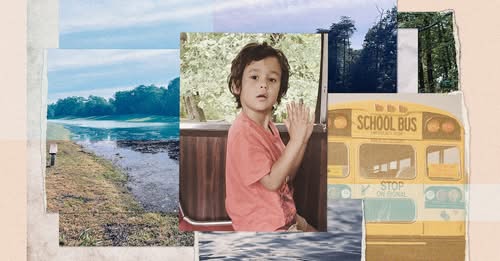

Five-year-old Miles McMahon drowned in a pond after fleeing his home. His death sparked change at his school and broader recognition of a danger facing a growing number of autistic children.

Five-year-old Miles McMahon drowned in a pond after fleeing his home. His death sparked change at his school and broader recognition of a danger facing a growing number of autistic children.

(Marissa Vonesh/The Washington Post; Jasmine Golden/The Washington Post; Courtesy of Dominique McMahon; iStock)

They didn’t expect the doorbell.

Or how it would be the sound that bisected their lives. Before. And after.

Dominique McMahon, a 32-year-old wife and mother of two, rushed to get dressed. The ringing was relentless.

“Where’s Miles?” she remembers asking aloud.

The question had grown to consume their days at home and those of his teachers at school in Charles County. Miles, a kindergartner, had autism and wasn’t yet speaking. He had been a wanderer since he could walk.

Miles had been able to slip away from his preschool class more than 700 times, a number the McMahons weren’t aware of until the end of the school year, according to school records obtained by The Washington Post. He liked to flee from his parents, too.

The McMahons knew opening the door too wide carried the risk that their younger son would make his move. An intricate maze of locks and bolts at home was meant to keep him safe from a world his 5-year-old mind never feared.

But on this day, Oct. 13, he didn’t approach the door.

Where’s Miles?

The neighbor on the front porch had an unsettling answer: Moments earlier, his wife had seen Miles outside, barefoot and alone.

How he got out didn’t make sense to Dominique, but in that moment it didn’t matter. She put on Crocs and grabbed her glasses. “It’s Miles!” she shouted to her husband Tom, 38. Then she ran.

The chase had been part of their lives as parents. Finding help for Miles had been a frustrating lesson in waiting: It took more than a year to get him seen by a doctor who could diagnose his autism and open doors for therapy at home. And despite his parents’ pleas and recommendations from teachers, the school district had not put him in its program for students with autism, where trained teachers might have helped with his behavior.

Now he was gone. The frantic 12-hour search felt like forever. It was after midnight when authorities found Miles, drowned in a nearby pond.

In the months that followed, the story of Miles’s life — and the tragic way it ended — reverberated through the community, bringing light to a challenge faced by a growing number of families. It prompted teachers at his school to call on school system leaders for more resources for children with autism and spurred a wave of safety measures for students. And, Miles’s death, along with that of another young boy from Maryland, triggered a new state law that requires schools to tell parents when their child flees from school, track the number of times and make a plan to address it.

Away from safety

The brand of fear that shadowed the McMahons is well known by parents raising autistic children. So, too, is the risk of a devastating outcome.

In Boise, Idaho, Matthew Glynn walked away from his 5th birthday party and drowned in a canal. In West Chester Township, Ohio, Joshua Al-Lateef Jr., 6, was reported missing and found dead in a pond near his apartment building. And in Hopkins, Minnesota, 4-year-old Waeys Mohamed drowned in a creek.

More children with autism died in 2024 after wandering away — 82 — than in any other year since the National Autism Association began tracking cases over 20 years ago, said Lori McIlwain,Source comment the association’s co-founder and executive director. So far this year, at least 75 children have died.

Experts in the field call the behavior “eloping.”

Autistic adults said eloping usually appears as a form of communicating an unmet need. It might reflect the desire to move toward an attraction or away from a threat. And it can be difficult for parents and guardians to understand.

“It’s a topic that strikes people as very intuitive, but it’s actually quite complicated,” said Zoe Gross, director of advocacy for D.C.-based Autistic Self Advocacy Network.

Autism, a condition with unclear causes that are under intense scrutiny by the Trump administration, is twice as prevalent in children as in 2010, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, part of a decades-long spike putting a strain on health care and schools, where nationwide teacher shortages are felt most acutely in special education.

While an exact reason for the surge in elopement is difficult to pinpoint, post-pandemic service disruptions and an increase in autism diagnoses at earlier ages may all play a part, McIlwain said.

Death by eloping nearly doubled from 2023 to 2024, according to data from the National Autism Association. Most were around Miles’s age and drowned not far from where they went missing, McIlwain said.

“Water is the mute button for everything,” McIlwain said. “If there’s water nearby, that’s where these kids are going to go.”

The Sunday morning that he disappeared, Miles had torn through the screen of the open living room window and jumped out. He was almost hit by a red pickup as he ran across the street, video from a neighbor’s doorbell camera showed.

He was headed toward a pond.

The McMahons had thought their door locks and the backyard fence they built and covered with a tarp to prevent him from climbing would be enough to keep Miles away from the road and the water.

‘Learning on our own’

The long struggle to keep Miles safe illustrates the daily danger parents confront and the isolation they often feel when dealing with the overwhelmed systems meant to help children with autism.

Dominique and Tom, both Air Force veterans who met during their active duty service, married in 2016. They soon started a family and settled in the Maryland community of Waldorf.

Aiden came first, in 2017, then Miles two years later.

At 1½ years old, they began to worry Miles wasn’t speaking or pointing much. Aiden behaved similarly when he was young but grew out of it.

But by 2, Miles still wasn’t communicating. A pediatrician suggested they put on “Sesame Street.”

Dominique thought he might be deaf. A hearing specialist confirmed that wasn’t the problem. The parents tried to start therapies for speech and social skills but couldn’t get Miles in anywhere during the pandemic.

One day, a mother at an early learning center who had a child with autism asked her, “Does your son have autism?”

It was a question she’d have trouble answering.

Miles waited for nearly two years, on three waiting lists, before being diagnosed in 2023, the McMahons said.

Catherine Lord, a professor at UCLA and clinical psychologist who specializes in autism research, said a diagnosis shouldn’t hinder families’ access to care, but it often does.

“It’s really unfortunate that it’s become a ticket to get services,” Lord said, “because you don’t really need a diagnosis to at least start things like working with families about potential unsafe situations.”

Even after Miles was diagnosed, Tom said they never received help for the behavior that scared them the most — his constant attempts to flee.

“It was a lot of learning on our own,” he said. “When you get diagnosed with cancer, you leave the cancer center with like a big packet of ‘this is what you can expect,’ you’re assigned a person, and there’s some kind of communication and dialogue to understand what this means and the things that you should be doing now, in the near future and for the rest of your life. When you get a formal diagnosis of autism, you don’t get any of that.”

Even on the run, Miles was the “happiest little boy you’ve ever seen,” Dominique said.

He loved to take things apart, from toys to lamps, and build dinosaurs, whales and sharks out of Play-Doh. After his diagnosis, he used a communication device that allowed him to press buttons to relay messages. But a smile was often how Miles conveyed his thoughts.

The world was so exciting to Miles that he couldn’t contain himself. Miles had learned how to carefully press his thumb down to wiggle off the wrist tether his parents had wound on his arm whenever they ventured out.

Even the most fun places for him, like outdoor playgrounds, were risky, most without fencing to keep him in. Miles would bolt into the woods, running knee-deep in leaves as his parents chased him.

Knowing water safety was a concern, the McMahons signed up their sons for swim lessons in the county, but the lessons weren’t designed for children like Miles.

They were also waiting for Miles’s turn for access to applied behavior analysis — ABA therapy — but were impeded by another waiting list.

Tom and Dominique showed Miles educational videos and programmed his communication device to reinforce their warnings that running away wasn’t safe. None of it worked.

‘A sobering reminder’

A few days after Miles’s death, a teacher who indicated she was speaking for her colleagues at Eva Turner Elementary School, where he’d been in his first months of kindergarten, sent an email to Charles County Public Schools leaders, citing a “lack of compassionate leadership.”

“Eva Turner is knowingly understaffed, lacks necessary resources required for the safety and education of their students, and are in a time of need,” she said, urging officials to address shortcomings in how it serves students with autism, including a “lack of lawful” individualized education program services. “The number of eloping students at Eva Turner constantly placing themselves in danger on the same roads we searched for Miles on is increasing daily.”

In the same email, the teacher said she kept a plastic ruler in her emergency exit door, along with two shelves blocking the door and a child safety lock on the front door. “Is this your temporary fix,” the teacher said to county schools leadership.

Charles County Public Schools Superintendent Maria Navarro, who declined to be interviewed, replied to the email that she was “keenly aware” of “several other deeply concerning incidents” at Turner.

The school’s principal was also raising red flags to school division leaders about limited staffing and the need for more support in SOAR, the program for students with autism, according to emails obtained by The Post.

During the 2024-2025 academic year at Eva Turner, at least four families, including the McMahons, claimed in emails to school leaders that the school system fell short in meeting federal requirements to follow education plans for their children’s special needs. Students with autism were regressing, these parents said.

One urgent concern raised repeatedly was eloping. In one email, a parent said their child fled from school grounds last fall and “ended up in the community” without clothes.

Miles would take off from unlocked classrooms or unfenced play areas. Once, in preschool, he escaped as far as the neighboring community swimming pool, where only the fence kept him from the water.

End of carousel

The McMahons said they received calls when Miles left school grounds, but not the hundreds of other times he ran from class.

Miles would return home with scratches on the back of his neck from teachers trying to catch him during his escape attempts, Dominique and Tom said in an email last July requesting that he be assessed for SOAR. “He has no awareness about his own safety and continues to run into the street and toward water.”

A school facilitator told them their initial email request to place Miles in SOAR, which they had made in February 2024, had been overlooked, according to the records obtained by The Post. School staff instead placed Miles in an “inclusion” kindergarten class, where he would receive special education support.

Andrea Bennett and Lisa Frank, special education and behavioral consultants in Maryland who work with families and schools through their business, Special Kids Company, said schools are “stuck between a rock and hard place” to follow inclusivity rules in federal disability law while ensuring a child’s safety.

In late September 2024, Tom visited the class and noticed his son didn’t have his communication device.

While in the room with the assistant principal, a teacher and three aides, Miles got up from eating cereal at his chair, walked behind them and ran out the door. “Forcing him to remain in the current classroom setting is hindering his educational and social-emotional progress,” Tom wrote in an email to school staff afterward.

Shelley Mackey, a spokeswoman for Charles County Public Schools, declined to respond to questions about specific complaints from families, citing student privacy.

Charles County Public Schools, including Eva Turner, did not comprehensively track how often special education students were escaping from class that school year, Mackey said in a statement. The McMahons found out because his preschool teacher was keeping a tally.

Daisha Miller, the parent of a third-grader who had been in the SOAR program for two years, twice saw students elope from the classroom last year; one nearly made it to the street with three teachers chasing behind, she said.

In the year since Miles’s death, the school system has ushered in several changes, including developing a plan to prevent student elopements. Teachers and staff received training. And class sizes are smaller in SOAR’s expanded program, with each having no more than 10 students, Mackey said.

Miller’s son attends a new school as part of those changes. She said the new system isn’t perfect, but she appreciates the steps the school system has taken.

Turner also hired an extra teaching assistant. A fence and a gate went up around the playground, and some doors were equipped with alarms. And the gate between the school and the community center is now locked during school hours, Mackey said in the statement, so that students can’t end up at the center’s swimming pool.

A new law prompted by Miles’s death will require schools to track a child’s elopements and elopement attempts, inform parents, and develop intervention plans.

“Miles’s story is a sobering reminder of what’s at stake,” Maryland state Del. Edith J. Patterson of Charles County wrote in a letter supporting the law she sponsored. “This behavior is not only dangerous but … potentially fatal.”

As of Oct. 1, 19 students have eloped this year across the Charles County Public Schools system, which defines elopement as leaving the school campus without permission, Mackey said. The school system does not track how many students leave class without permission.

Forever changed

The McMahons’ once-active home sounds mostly quiet. No longer are there two brothers chasing their pit bull Clyde in the backyard or eating Popsicles.

“We mourn the love that we can no longer give to him,” Dominique said. “Every day that passes, I feel like I’m getting further and further away from Miles. And I’m afraid I’ll forget things about him that I really want to hold on to.”

They are haunted by a question that can’t be answered: With more help, would Miles still be here?

While the state law is aimed at preventing elopement from schools, the McMahons also hope their story can make communities safer. They’ve pushed for a law to require fencing around bodies of water in residential areas that would keep kids out.

On the family’s schedule the same week Miles went missing and never came home: a meeting with school staff to review his individualized education program, an in-home training visit by a behavioral therapist and a class field trip to the pumpkin patch.

When the “Moana” or “Lion King” soundtrack or his favorite song, “Heads, Shoulders, Knees and Toes,” plays on the Alexa, joy is now sadness.

“He’s everywhere, but nowhere,” Tom said. “Every day we have to come back to that realization.”